ANTIBIOTIC STEWARDSHIP TOOLKIT

FOR DENTAL PROVIDERS

NOVEMBER 2017

Printed by Authority of the State of Illinois

P.O. # 273029 350 11/2017

1

Antibiotics Stewardship Toolkit for Dental Providers

The purpose of this toolkit is to provide Illinois dentists with resources to support appropriate antibiotic

prescribing as part of the Illinois Precious Drugs & Scary Bugs Campaign. The campaign aims to promote the

judicious use of antibiotics in the outpatient setting. Antibiotic resistance is among the greatest public health

threats today, leading to 2 million infections and 23,000 deaths each year

1

. In community settings in the

United States, dentists are the fourth highest prescribers of antibiotics and have an important role to play to

ensure that antibiotics are prescribed only:

when needed;

at the right dose;

for the right duration; and

at the right time.

2

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends that all outpatient health care providers,

including dentists, take steps to measure and improve how antibiotics are prescribed using the Core Elements

of Outpatient Antibiotic Stewardship as a framework. The four core elements include:

Commitment: Demonstrate dedication to optimizing antibiotic prescribing and patient safety

Action for Policy and Practice: Implement a practice change to improve antibiotic prescribing

Tracking and Reporting: Monitor antibiotic prescribing practices

Education and Expertise: Provide educational resources to health care providers and patients

This toolkit is organized around these core elements and includes provider and patient resources. It is

intended to be used as a practical action planning guide. For more information please visit

www.cdc.com/antibiotic-use or e-mail DPH.DPSQ@Illinois.gov.

Funding for this toolkit was made possible by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The views expressed in

this document do not necessarily reflect the official policies of the US Department of Health and Human Services, nor

does the mention of trade names, commercial practices, or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. Government.

1

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2017). Antibiotic/Antimicrobial Resistance. Available at:

https://www.cdc.gov/drugresistance/index.html

2

Roberts, et. al. (2013). Antibiotic prescribing by general dentists in the United States. Available at:

http://jada.ada.org/article/S0002-8177(16)30942-4/fulltext

2

Contents Page

INTRODUCTION

Gubernatorial Proclamation……………………………………………………………………………………………….…………..…………..….…3

The Need…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..……..…..…..4

What YOU Can Do: Core Elements of Outpatient Antibiotic Stewardship……………………………………………………..…..5

1. MAKE A COMMITMENT………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..….….….6

You can demonstrate commitment to optimizing antibiotic prescribing and patient safety by:

Submitting a letter of commitment to IDPH

Displaying a customizable commitment poster

2. ACT

Use evidence-based diagnostic criteria and treatment recommendations to improve

antibiotic prescribing with the resources provided.

Evidence-based Practices

Checklist for Antibiotic Prescribing in Dentistry …………………………………………………………………………….….……..10

Combating Antibiotic Resistance ……………………………………………………………………………………………………..………11

Antibiotic Prophylaxis Update 2017 ……………………………………………………………………………………………………..….15

Treatment Guidelines

Use of Antibiotic Therapy for Pediatric Patients ……………………………………………………………………………………...18

Management of Patients with Prosthetic Joints – Chairside Guideline ………………………………………………….…21

Nonsurgical Treatment of Chronic Periodontitis by Scaling and Root Planing……………………………………..……22

3. TRACK AND REPORT

Implement at least one system to track and report antibiotic prescribing. Page 24 includes resources for

outcome tracking and continuing medical education. Please complete a self-evaluation of your prescribing

practices by January 5, 2018 using the survey provided.

Illinois Dental Provider Survey

4. EDUCATE

Educate patients about appropriate antibiotic use and the potential harms of antibiotic

treatment with these resources:

Antibiotic Safety : Do’s & Don’ts at the Dentist…………………………………………………………………………….………….26

What is Antibiotic Prophylaxis? ....................................................................................................................27

What is Infective Endocarditis?.....................................................................................................................28

Improving Antibiotic Use …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………....…..30

REFERENCES……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..….………….…..32

1

l 7 it·Sl -/

SECRETARY OF STATE

GOVERNOR

3

4

The Need

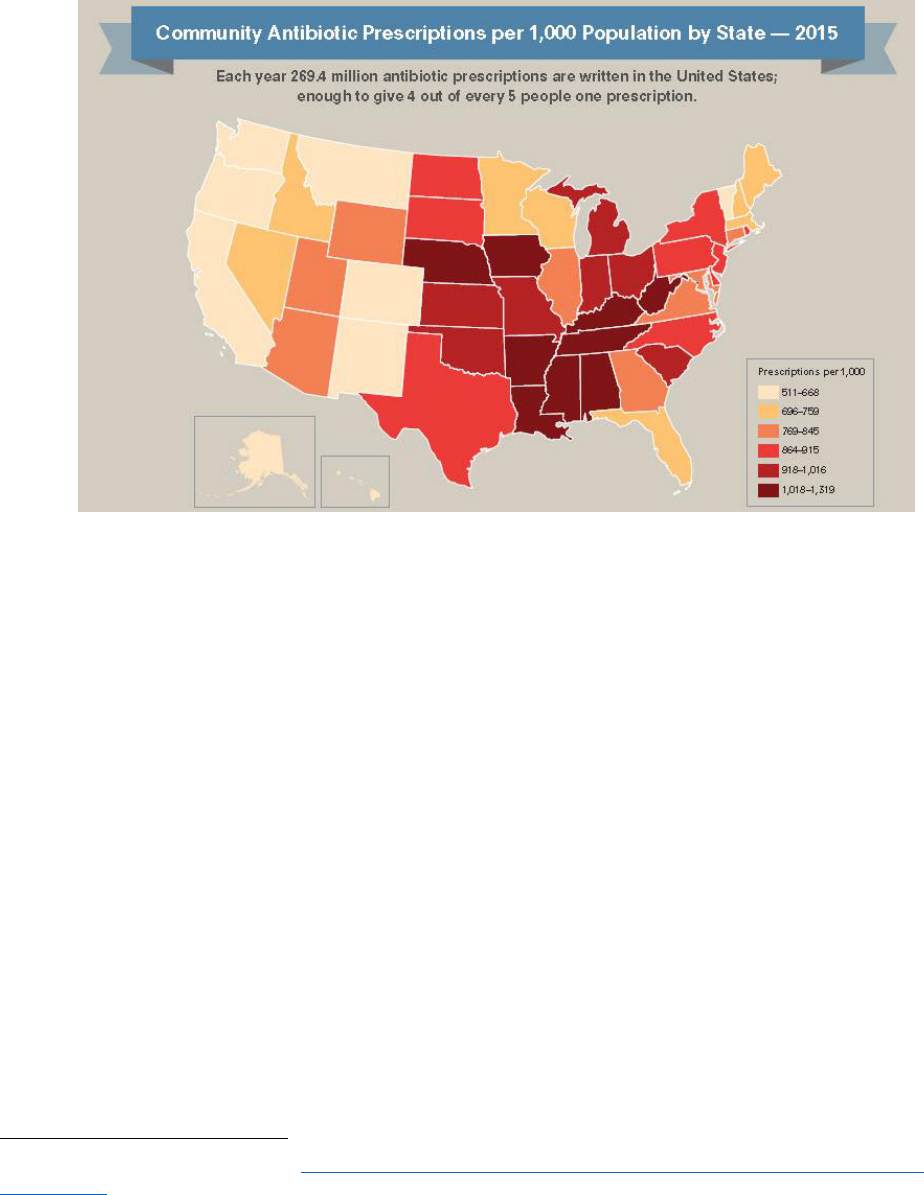

Antibiotic Prescribing in Outpatient Settings in the United States

Over 60% of all antibiotic expenditures are associated with the outpatient setting.

At least 30% of antibiotics prescribed in the outpatient setting are unnecessary.

3

Antibiotic Prescribing Among Dentists in the United States

Dentists account for 10% of outpatient antibiotic prescriptions, or 24.5 million prescriptions. In 2013,

dentists wrote an average of 205 antibiotic prescriptions each.

Overall, in the United States dentists prescribe 77.5 prescriptions per 1,000 people.

Illinois dentists prescribe, on average, 79.6 prescriptions per 1,000 people (higher than the national

average).

Among dentists, the three highest prescribed types of antibiotics are penicillin (69.6%), lincosamides

(14.6%), and macrolides (5.4%).

4

Unintended Consequences of Antibiotic use

Adverse events from antibiotics include rashes, diarrhea, and severe allergic reactions. These lead to an

average of 143,000 emergency department visits each year and contribute to excess health care costs.

5

Antibiotic treatment is the most important risk factor for Clostridium difficile infection, which can cause

life-threatening diarrhea. A 2013 study found that over 40% of patients with C. difficile infection visited

a dentist or physician’s office in the preceding four months.

6

3

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: https://www.cdc.gov/antibiotic-use/community/programs-measurement/measuring-antibiotic-

prescribing.html

4

Roberts, R., Bartoces, M., Thompson, S. and Hicks, L. (2017). Antibiotic prescribing by general dentists in the United States, 2013. The Journal of the

American Dental Association, 148(3), pp.172-178.e1.

5

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: https://www.cdc.gov/medicationsafety/program_focus_activities.html

6

Roberts, R., Bartoces, M., Thompson, S. and Hicks, L. (2017). Antibiotic prescribing by general dentists in the United States, 2013. The Journal of the

American Dental Association, 148(3), pp.172-178.e1.

6

1. MAKE A COMMITMENT

A commitment from your dental office to prescribe antibiotics appropriately and

engage in antibiotic stewardship is critical to improving antibiotic prescribing.

Here are some ways your dental office can demonstrate commitment:

Submit the enclosed statement of commitment to the Illinois Department of

Public Health (IDPH). Providers making a commitment can choose to be

recognized on IDPH’s Website at www.tinyurl.com/drugsandbugs.

Display public commitment to antibiotic stewardship in your office (see sample

templates on page 7).

Include antibiotic stewardship-related duties in position descriptions or job

evaluation criteria.

Educate all staff members on how to manage patient expectations about

appropriate antibiotic use.

9

2. Act

Dentists can implement policies and interventions to promote appropriate antibiotic

prescribing.

Use evidence-based diagnostic criteria and treatment recommendations

Evidence Based Practices

Checklist for Antibiotic Prescribing in Dentistry (page 10)

o Download here: http://tinyurl.com/dentalabxlist

Combating Antibiotic Resistance (page 11)

Antibiotic Prophylaxis Update 2017 (page 15)

Treatment Guidelines

Guideline on the use of Antibiotic Therapy for Pediatric Patients (page 18)

Management of Patients with Prosthetic Joints – Chairside Guide (page 21)

Nonsurgical Treatment of Chronic Periodontitis by Scaling and Root Planing

with or without Adjuncts: Clinical Practice Guideline (page 22)

Review communications skills training for clinicians

Drexel University College of Medicine Physician Communication Modules:

interactive modules designed to enhance physician and patient

communication and address patient attitudes and beliefs that more care is

better care.

o Link to modules: http://tinyurl.com/cwmodules

CS267105-1

National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases

Division of Healthcare Quality Promotion

Checklist for Antibiotic Prescribing in Dentistry

Pretreatment

Correctly diagnose an oral bacterial infection.

Consider therapeutic management interventions, which may be sufficient to

control a localized oral bacterial infection.

Weigh potential benefits and risks (i.e., toxicity, allergy, adverse effects,

Clostridium difficile infection) of antibiotics before prescribing.

Prescribe antibiotics only for patients of record and only for bacterial infections

you have been trained to treat. Do not prescribe antibiotics for oral viral

infections, fungal infections, or ulcerations related to trauma or aphthae.

Implement national antibiotic prophylaxis recommendations for the medical

concerns for which guidelines exist (e.g., cardiac defects).

Assess patients’ medical history and conditions, pregnancy status, drug

allergies, and potential for drug-drug interactions and adverse events, any of

which may impact antibiotic selection.

Prescribing

Ensure evidence-based antibiotic references are readily available during

patient visits. Avoid prescribing based on non-evidence-based historical

practices, patient demand, convenience, or pressure from colleagues.

Make and document the diagnosis, treatment steps, and rationale for antibiotic

use (if prescribed) in the patient chart.

Prescribe only when clinical signs and symptoms of a bacterial infection

suggest systemic immune response, such as fever or malaise along with local

oral swelling.

Revise empiric antibiotic regimens on the basis of patient progress and, if

needed, culture results.

Use the most targeted (narrow-spectrum) antibiotic for the shortest duration

possible (2-3 days after the clinical signs and symptoms subside) for otherwise

healthy patients.

Discuss antibiotic use and prescribing protocols with referring specialists.

Patient Education

Educate your patients to take antibiotics exactly as prescribed, take antibiotics

prescribed only for them, and not to save antibiotics for future illness.

Staff Education

Ensure staff members are trained in order to improve the probability of patient

adherence to antibiotic prescriptions.

https://www.cdc.gov/antibiotic-use/community/downloads/dental-fact-sheet-FINAL.pdf

10

484 JADA, Vol. 135, April 2004

J

A

D

A

C

O

N

T

I

N

U

I

N

G

E

D

U

C

A

T

I

O

N

✷

✷

®

ASSOCIATION REPORT

A

R

T

I

C

L

E

1

Background. The ADA Council on Sci-

entific Affairs developed this report to pro-

vide dental professionals with current infor-

mation on antibiotic resistance and related

considerations about the clinical use of

antibiotics that are unique to the practice of

dentistry.

Overview. This report addresses the

association between the overuse of antibi-

otics and the development of resistant bac-

teria. The Council also presents a set of

clinical guidelines that urges dentists to

consider using narrow-spectrum antibacte-

rial drugs in simple infections to minimize

disturbance of the normal microflora, and to

preserve the use of broad-spectrum drugs

for more complex infections.

Conclusions and Practice

Implications. The Council recommends

the prudent and appropriate use of antibac-

terial drugs to prolong their efficacy and

promotes reserving their use for the man-

agement of active infectious disease and the

prevention of hematogenously spread infec-

tion, such as infective endocarditis or total

joint infection, in high-risk patients.

Combating antibiotic

resistance

ADA COUNCIL ON SCIENTIFIC AFFAIRS

F

or the past 70 years, antibiotic therapy has

been a mainstay in the treatment of bacterial

infectious diseases. However, widespread use

of these drugs by the health professions and

the livestock industry has resulted in an

alarming increase in the prevalence of drug-resistant

bacterial infections.

Worldwide, many strains of Staphylococcus aureus

exhibit resistance to all medically important antibacte-

rial drugs, including vancomycin,

1,2

and methicillin-

resistant S. aureus is one of the most frequent nosoco-

mial pathogens.

3

In the United States,

the proportion of Streptococcus pneumo-

niae isolates with clinically significant

reductions in susceptibility to β lactam

antimicrobial agents has increased

more than threefold.

4,5

Even more

alarming is the rate at which bacteria

develop resistance; microorganisms

exhibiting resistance to new drugs often

are isolated soon after the drugs have

been introduced.

6

This growing problem

has contributed significantly to the mor-

bidity and mortality of infectious dis-

eases, with death rates for communi-

cable diseases such as tuberculosis

rising again.

7,8

Disease etiologies also are changing.

In recent studies, staphylococci, particu-

larly S. aureus, have surpassed viridans

streptococci as the most common cause

of infective endocarditis.

9

Resistance

among bacteria of the oral microflora is

increasing as well. During the past decade, retrospec-

tive analyses of clinical isolates have clearly docu-

mented an increase in resistance in the viridans strep-

Any perceived

potential

benefit of

antibiotic

prophylaxis

must be

weighed

against the

known risks of

antibiotic

toxicity, allergy

and the

development,

selection and

transmission

of microbial

resistance.

tococci.

10

Further, strains of virtually

every oral microorganism tested exhibit

varying degrees of resistance to various

antibacterial agents.

11

This increase in antibacterial resis-

tance has been attributed primarily to

two different processes. First, reduced

susceptibility may develop via genetic

mutations that spontaneously confer a

newly resistant phenotype.

12

Alterna-

tively, the exchange of resistant deter-

minants between sensitive and resis-

tant microorganisms (of the same or

different species) may occur.

13

Regard-

less of the genetic basis of resistance,

the selective pressure exerted by

widespread use of antibacterial drugs is

the driving force behind this public

health problem. It is only through the

prudent and appropriate use of antibac-

terial drugs that their efficacy may be

prolonged.

Antibacterial drugs should be

ABSTRACT

Copyright ©2004 American Dental Association. All rights reserved.

11

Available online: http://jada.ada.org/article/S0002-8177(14)61234-4/pdf

JADA, Vol. 135, April 2004 485

ASSOCIATION REPORT

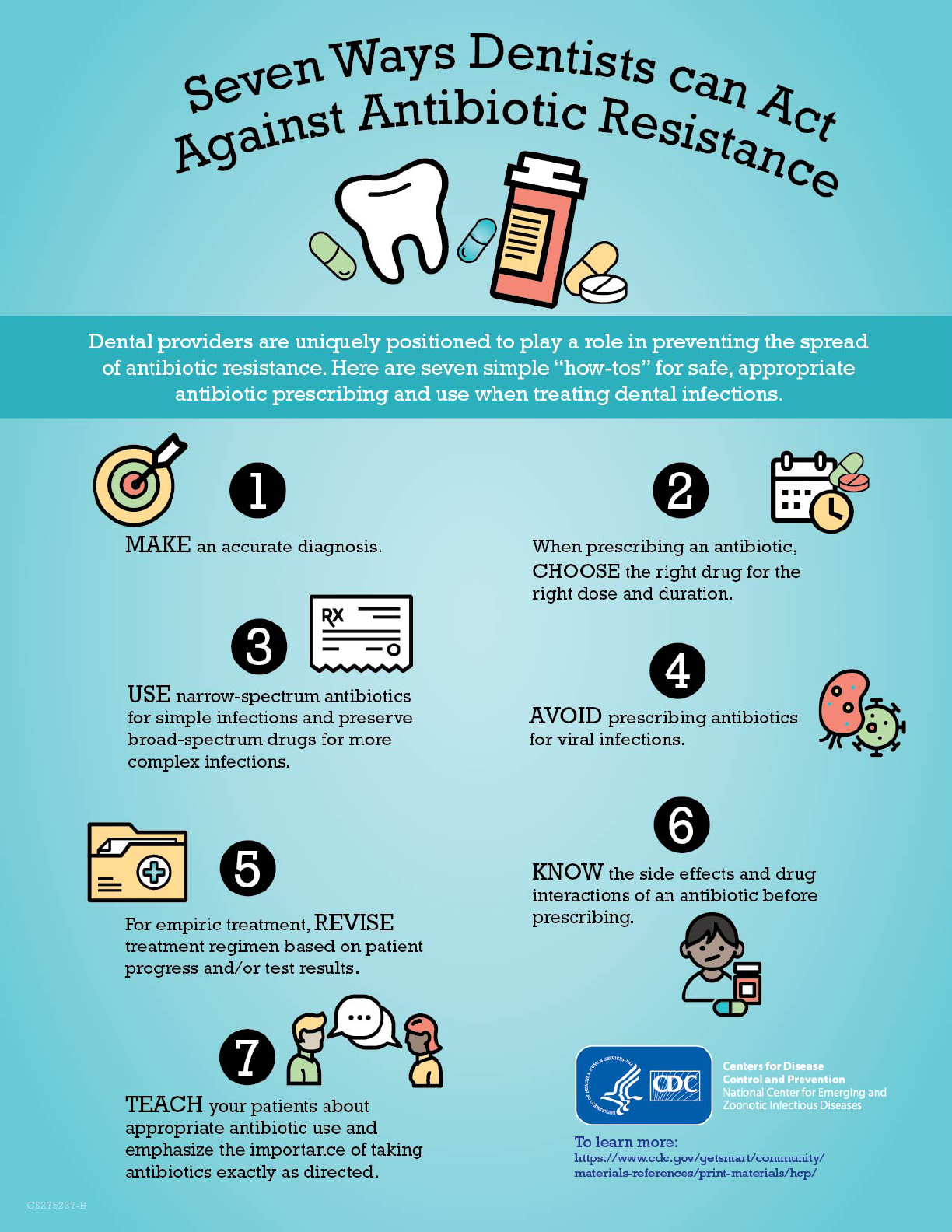

(1) make an accu-

rate diagnosis;

(2) use appropriate

antibiotics and dosing

schedules;

(3) consider using

narrow-spectrum

antibacterial drugs

(Table 1) in simple

infections to minimize

disturbance of the

normal microflora, and

preserve the use of

broad-spectrum drugs

(Table 2) for more com-

plex infections

17

;

(4) avoid unneces-

sary use of antibacte-

rial drugs in treating

viral infections;

(5) if treating empiri-

cally, revise treatment

regimen based on

patient progress or test

results;

(6) obtain thorough

knowledge of the side

effects and drug inter-

actions of an antibacte-

rial drug before pre-

scribing it;

(7) educate the

patient regarding

proper use of the drug

and stress the importance of completing the full

course of therapy (that is, taking all doses for the

prescribed treatment time).

Furthermore, the diagnosis and antibiotic

selection should be based on a thorough history

(medical and dental) to reveal or avoid adverse

reactions, such as allergies and drug interactions.

Any perceived potential benefit of antibiotic pro-

phylaxis must be weighed against the known

risks of antibiotic toxicity, allergy and the devel-

opment, selection and transmission of microbial

resistance.

15

It remains incumbent on dental practitioners,

as health care providers, to use antibacterial

drugs in a prudent and appropriate manner.

Adherence to the principles outlined here will aid

in extending the efficacy of the antibacterial

drugs that form the treatment foundation for

many infectious diseases. ■

reserved for the management of active infectious

disease and considered for the prevention of

hematogenously spread infection, such as infec-

tive endocarditis or total joint infection, in high-

risk patients (as defined by the American Heart

Association

14

and the American Dental Associa-

tion and the American Academy of Orthopedic

Surgeons

15

). One example of their use in man-

aging infectious disease is in the treatment of

aggressive periodontal disease, which use has

become well-accepted for optimal control of the

disease process.

16

The Council encourages further

research on the appropriate use of antibacterial

therapy in the management of oral diseases.

GUIDELINES FOR PRESCRIBING

ANTIBIOTICS

The following guidelines should be observed when

prescribing antibacterial drugs:

TABLE 1

NARROW-SPECTRUM* ANTIMICROBIAL AGENTS

ENCOUNTERED IN DENTISTRY.

†

GENERIC NAME CHARACTERISTICS

‡

COMMON INDICATIONS

FOR USE

Indicated for the

treatment of infections

caused by susceptible

microorganisms; used as a

prophylactic antibiotic in

high-risk patients allergic

to penicillin for the

prevention of both

bacterial endocarditis and

infections of total joint

replacements

Has been used as adjunct

in treatment of periodon-

titis and acute necrotizing

ulcerative gingivitis;

commonly coprescribed

with amoxicillin (Note: its

combined use with amoxi-

cillin or amoxicillin/

clavulanic acid has not

been approved by the U.S.

Food and Drug Adminis-

tration)

Use is limited to treatment

of minor infections such as

ulcerative gingivostom-

atitis, and to the prophy-

laxis and continued treat-

ment of streptococcal

infections

Clindamycin

Metronidazole

Penicillin V

Potassium

Bacteriostatic (bactericidal

at higher doses); active

against some aerobic gram-

positive cocci (including

Staphylococcus aureus, S.

epidermidis, streptococci and

pneumococci), some anaerobic

gram-negative bacilli, many

anaerobic gram-positive

non–spore-forming bacilli,

many anaerobic gram-positive

cocci and clostridia

Bactericidal; active against

most anaerobic cocci and both

gram-negative bacilli and

gram-positive spore-forming

bacilli

Bactericidal; cell-wall syn-

thesis inhibitor that is active

primarily against gram-

positive cocci (including

S. aureus), gram-positive and

gram-negative bacilli, and

spirochetes

* Active against a small number of organisms.

† Adapted in part from Ciancio.

17

‡ Bactericidal drugs directly kill an infecting organism; bacteriostatic drugs inhibit the proliferation of

bacteria by interfering with an essential metabolic process.

Copyright ©2004 American Dental Association. All rights reserved.

12

486 JADA, Vol. 135, April 2004

ASSOCIATION REPORT

TABLE 2

BROAD-SPECTRUM* ANTIMICROBIAL AGENTS ENCOUNTERED IN DENTISTRY.

†

GENERIC NAME CHARACTERISTICS

‡

COMMON INDICATIONS FOR USE

Commonly used as an empirical antibiotic for oral infec-

tions, sinusitis and skin infections; used as a prophylactic

antibiotic in high-risk patients for the prevention of bacte-

rial endocarditis and infections of total joint replacements

Used for the treatment of sinus, oral and respiratory

infections

Commonly used as an empirical antibiotic for oral infec-

tions, sinusitis and skin infections; used as a prophylactic

antibiotic in high-risk patients unable to take oral

medication for the prevention of both bacterial endocarditis

and total joint infections

Indicated for the treatment of infections caused by

susceptible microorganisms; used as a prophylactic

antibiotic in high-risk patients for the prevention of bacte-

rial endocarditis and infections of total joint replacements;

caution should be exercised when prescribing

cephalosporins for patients sensitive to penicillin

§

Used for the treatment of respiratory, urinary tract, skin

and biliary infections and for the treatment of septicemia

and endocarditis; used as a prophylactic antibiotic in high-

risk patients who are unable to take oral medications for

the prevention of both bacterial endocarditis and infections

of total joint replacements; caution should be exercised

when prescribing cephalosporins for patients sensitive to

penicillin

§

Indicated for the treatment of infections caused by

susceptible microorganisms; used as a prophylactic

antibiotic in high-risk patients for the prevention of bacte-

rial endocarditis and infections of total joint replacements;

caution should be exercised when prescribing

cephalosporins for patients sensitive to penicillin

§

Used as a prophylactic antibiotic in high-risk patients for the

prevention of bacterial endocarditis and infections of total

joint replacements; caution should be exercised when pre-

scribing cephalosporins for patients sensitive to penicillin

§

Indicated for the treatment of mild-to-moderate infections

caused by susceptible microorganisms; used as a

prophylactic antibiotic in high-risk patients allergic to

penicillin for the prevention of bacterial endocarditis

Indicated for the treatment of mild-to-moderate infections

caused by susceptible microorganisms; used as a prophy-

lactic antibiotic in high-risk patients allergic to penicillin

for the prevention of bacterial endocarditis

Indicated for the treatment of infections of upper and

lower respiratory tract, skin and soft-tissue infections of

mild-to-moderate severity; alternative to penicillin G and

other penicillins for treatment of gram-positive coccoid infec-

tions in patients with hypersensitivity to penicillins; used as

a prophylactic antibiotic in high-risk patients allergic to

penicillin for the prevention of bacterial endocarditis

Indicated for the treatment of periodontitis and acute

necrotizing ulcerative gingivitis (Note: to avoid the

gastrointestinal side effects of oral tetracyclines, localized

delivery systems of doxycycline and minocycline are

marketed for the treatment of periodontitis)

Amoxicillin

(Semisynthetic

Penicillin)

Amoxicillin

With

Clavulanic Acid

Ampicillin

(Semisynthetic

Penicillin)

Cefadroxil

(First-

Generation

Cephalosporin)

Cefazolin

(First-

Generation

Cephalosporin)

Cephalexin

(First-

Generation

Cephalosporin)

Cephradine

(First-

Generation

Cephalosporin)

Azithromycin

(Macrolide)

Clarithromycin

(Macrolide)

Erythromycin

(Macrolide)

Tetracycline

(Doxycycline,

Minocycline)

Bactericidal; active against many

gram-negative and gram-positive

organisms; not effective against

β-lactamase–producing bacteria

Bactericidal; active against a wide

spectrum of gram-negative and

gram-positive organisms, including

β-lactamase–producing bacteria

Bactericidal; active against many

gram-negative and gram-positive

organisms; not effective against

β-lactamase–producing bacteria

Bactericidal; active against

β-hemolytic streptococci,

staphylococci, Streptococcus pneumo-

niae, Escherichia coli, Proteus

mirabilis, Klebsiella and Moraxella

Bactericidal; active against group A

β-hemolytic streptococci,

Haemophilus influenzae, S. pneumo-

niae, E. coli, Enterobacter aerogenes,

P. mirabilis and Klebsiella

Bactericidal; active against β-

hemolytic streptococci, staphylococci,

S. pneumoniae, E. coli, P. mirabilis,

Klebsiella and Moraxella

Bactericidal; active against group A

β-hemolytic streptococci, H. influenza,

S. pneumoniae, E. coli, E. aerogenes,

P. mirabilis and Klebsiella

Bactericidal; active against a wide

range of aerobic gram-negative and

gram-positive organisms

Bactericidal; active against a wide

spectrum of aerobic and anaerobic

gram-positive and gram-negative

organisms

Bacteriostatic; active against

gram-positive bacteria, particularly

gram-positive cocci; provides limited

activity against gram-negative

bacteria

Bacteriostatic; active against

gram-positive and gram-negative

bacteria, mycoplasmas, rickettsial

and chlamydial infections

* Used as empirical antibiotics or when culture and sensitivity testing are not available.

† Adapted in part from Ciancio.

17

‡ Bactericidal drugs directly kill an infecting organism; bacteriostatic drugs inhibit the proliferation of bacteria by interfering with an

essential metabolic process.

§ Cross-hypersensitivity has been documented and will occur in up to 10 percent of patients who have a history of penicillin allergy.

18

Copyright ©2004 American Dental Association. All rights reserved.

13

JADA, Vol. 135, April 2004 487

ASSOCIATION REPORT

Address reprint requests to ADA Council on Scientific Affairs, 211 E.

Chicago Ave., Chicago, Ill. 60611.

1. Smith TL, Pearson ML, Wilcox KR, et al. Emergence of

vancomycin resistance in Staphylococcus aureus. Glycopeptide-

Intermediate Staphylococcus aureus Working Group. N Engl J Med

1999;340:493-501.

2. Fridkin SK. Vancomycin-intermediate and -resistant Staphylo-

coccus aureus: what the infectious disease specialist needs to know.

Clin Infect Dis 2001;32(1):108-15.

3. Flournoy DJ. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus at a Vet-

erans Affairs Medical Center (1986-96). J Okla State Med Assoc

1997;90(6):228-35.

4. Istre GR, Tarpay M, Anderson M, Pryor A, Welch D. Pneumococcus

Study Group. Invasive disease due to Streptococcus pneumoniae in an

area with a high rate of relative penicillin resistance. J Infect Dis

1987;156:732-5.

5. Breiman RF, Spika JS, Navarro VJ, Darden PM, Darby CP. Pneu-

mococcal bacteremia in Charleston County, South Carolina: a decade

later. Arch Intern Med 1990;150:1401-5.

6. Stratton CW. Dead bugs don’t mutate: susceptibility issues in the

emergence of bacterial resistance. Emerg Infect Dis 2003;9(1):10-6.

7. Khan K, Muennig P, Behta M, Zivin JG. Global drug-resistance

patterns and the management of latent tuberculosis infection in immi-

grants to the United States. N Engl J Med 2002;347(23):1850-9.

8. Musoke RN, Revathi G. Emergence of multidrug-resistant gram-

negative organisms in a neonatal unit and the therapeutic implica-

tions. J Trop Pediatr 2000;46(2):86-91.

9. Mylonakis E, Calderwood SB. Infective endocarditis in adults.

N Engl J Med 2001;345(18):1318-30.

10. Doern GV, Ferraro MJ, Brueggemann AB, Ruoff KL. Emergence

of high rates of antimicrobial resistance among viridans group strepto-

cocci in the United States. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 1996;40:

891-4.

11. Jorgensen MG, Slots J. The ins and outs of periodontal antimicro-

bial therapy. J Calif Dent Assoc 2002;30(4):297-305.

12. Normark BH, Normark S. Evolution and spread of antibiotic

resistance. J Inter Med 2002;252(2):91-106.

13. Kozlova EV, Pivovarenko TV, Malinovskaia IV, Aminov RI,

Kovalenko NK, Voronin AM. Antibiotic resistance of Lactobacillus

strains [in Russian]. Antibiot Khimioter 1992;37(6):12-5.

14. Dajani AS, Taubert KA, Wilson W, et al. Prevention of bacterial

endocarditis: recommendations by the American Heart Association.

JADA 1997;128:1142-51.

15. American Dental Association; American Academy of Orthopedic

Surgeons. Antibiotic prophylaxis for dental patients with total joint

replacements. JADA 2003;134:895-9.

16. Herrera D, Sanz M, Jepsen S, Needleman I, Roldan S. A system-

atic review on the effect of systemic antimicrobials as an adjunct to

scaling and root planing in periodontitis patients. J Clin Periodontol

2002;29(supplement 3):136-59.

17. Ciancio SG, ed. ADA guide to dental therapeutics. 3rd ed.

Chicago: ADA Publishing; 2003:136-72.

18. Physicians’ desk reference. 58th ed. Montvale, N.J.: Medical

Economics; 2004:1321.

Copyright ©2004 American Dental Association. All rights reserved.

14

AAE Quick Reference Guide on Antibiotic Prophylaxis 2017 Update | Page 1

AAE Quick Reference Guide

Endocarditis Prophylaxis Recommendations

These recommendations are taken from 2017 American Heart Association and

American College of Cardiology focused update of the 2014 AHA/ADA Guideline

for Management of Patients with Valvular Disease (1) and cited by the ADA (2).

Prophylaxis against infective endocarditis is reasonable before dental

procedures that involve manipulation of gingival tissue, manipulation of the

periapical region of teeth, or perforation of the oral mucosa in patients with the

following:

In 2017, the AHA and American College of Cardiology (ACC) published

a focused update (5) to their previous guidelines on the management of

valvular heart disease. This reinforced their previous recommendations that

AP is reasonable for the subset of patients at increased risk of developing

IE and at high risk of experiencing adverse outcomes from IE (5). Their key

recommendations were:

1. Prosthetic cardiac valves, including transcatheter-implanted

prostheses and homografts.

2. Prosthetic material used for cardiac valve repair, such as

annuloplasty rings and chords.

3. Previous IE.

4. Unrepaired cyanotic congenital heart disease or repaired congenital

heart disease, with residual shunts or valvular regurgitation at the

site of or adjacent to the site of a prosthetic patch or prosthetic

device.

5. Cardiac transplant with valve regurgitation due to a structurally

abnormal valve.

Distribution Information

AAE members may reprint

this position statement for

distribution to patients or

referring dentists.

Antibiotic Prophylaxis

2017 Update

The guidance in this

statement is not intended

to substitute for a clinician’s

independent judgment in

light of the conditions and

needs of a specific patient.

About This Document

This paper is designed to

provide scientifically based

guidance to clinicians

regarding the use of antibiotics

in endodontic treatment.

Thank you to the Special

Committee on Antibiotic Use in

Endodontics: Ashraf F. Fouad,

Chair, B. Ellen Byrne, Anibal R.

Diogenes, Christine M. Sedgley

and Bruce Y. Cha.

©2017

Reprinted with permission from the

Am

erican Association of Endodontists.

Access additional resources at www.aae.org

In 2017, the ADA reaffirmed the recommended regimen as

follows.

Regimen:

Single Dose 30

to 60 min.

Before

Procedure

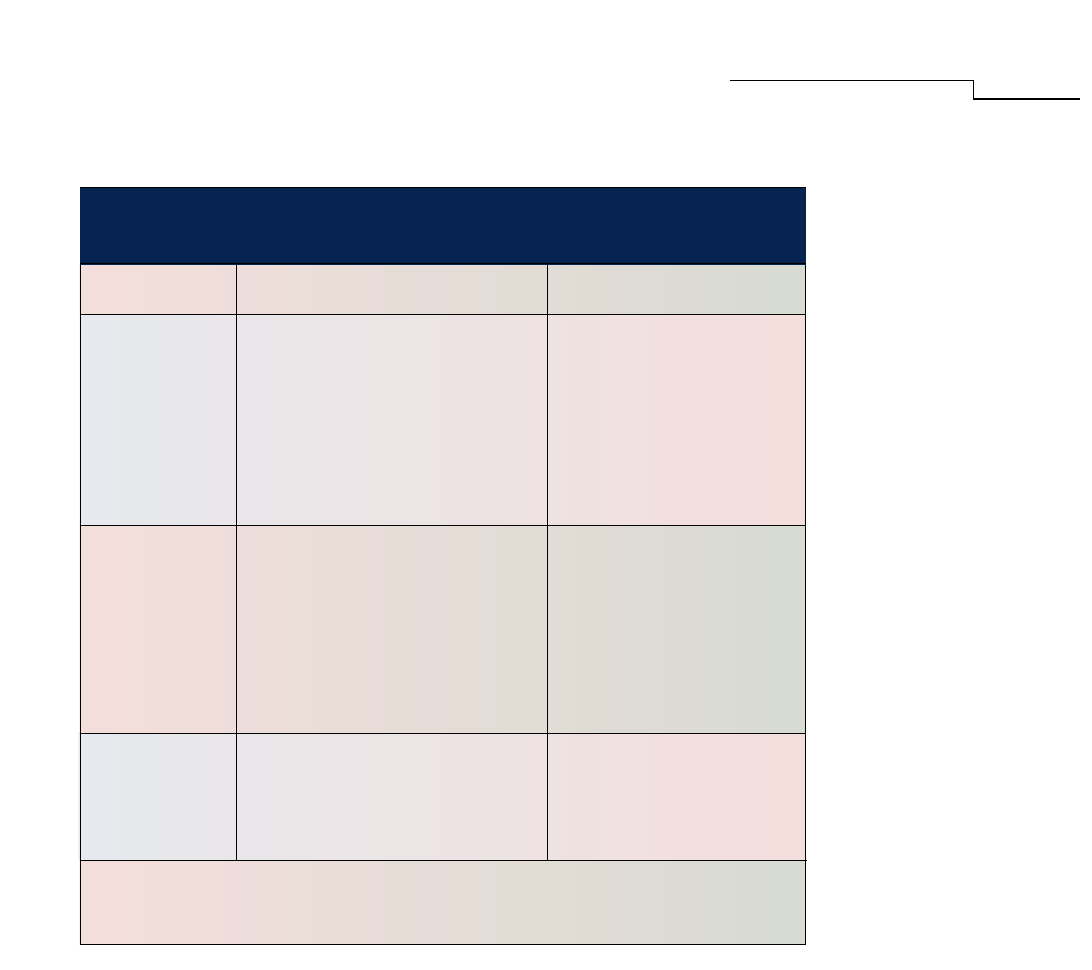

Situation Agent Adults Children

Oral Amoxicillin 2 g 50 mg/kg

Unable to take

oral medication

Ampicillin

OR

Cefazolin or

ceftriaxone

2 g IM* or IV+

1 g IM or IV

50 mg/kg IM

or IV

50 mg/kg IM

or IV

Allergic to

penicillins or

ampicillin—oral

OR

Clindamycin

OR

Azithromycin or

clarithromycin

2 g

600 mg

500 mg

50 mg/kg

20 mg/kg

15 mg/kg

Allergic to

penicillins or

ampicillin and

unable to take

oral medication

Cefazolin or

OR

Clindamycin

1 g IM or IV

600 mg IM or IV

50 mg/kg IM

or IV

20 mg/kg IM

or IV

*IM: Intramuscular

+IV: Intravenous

adult or pediatric dosage.

anaphylaxis, angioedeme, or urticaria with penecillins or ampicillin.

The ADA and AHA have a downloadable wallet card available

to providers at no cost to educate patients who may be at

risk for IC. http://www.heart.org/idc/groups/heart-public/@

wcm/@hcm/documents/downloadable/ucm_448472.pdf

Patients with Join Replacement

The following recommendation is taken from the ADA

Chairside Guide (© ADA 2015)

• In general, for patients with prosthetic joint implants,

prophylactic antibiotics are not recommended prior to

dental procedures to prevent prosthetic joint infection.

• In cases where antibiotics are deemed necessary, it is most

appropriate that the orthopedic surgeon recommend the

appropriate antibiotic regimen and when reasonable write

the prescription

Additional Considerations

The practitioner and patient should consider possible

clinical circumstances that may suggest the presence of a

significant medical risk in providing dental care without

or widespread antibiotic use. As part of the evidence-based

approach to care, this clinical recommendation should be

integrated with the practitioner’s professional judgment in

consultation with the patient’s physician, and the patient’s

needs and preferences.

• These considerations include, but are not limited to:

• Patients with previous late artificial joint infection

• Increased morbidity associated with joint surgery (wound

drainage/hematoma)

• Patients undergoing treatment of severe and spreading

oral infections (cellulitis)

• Patient with increased susceptibility for systemic infection

•

• Patients on immunosuppressive medications

• Diabetics with poor glycemic control

• Patients with systemic immunocompromising disorders

(e.g. rheumatoid arthritis, lupus erythematosus)

• Patient in whom extensive and invasive procedures are

planned

• Prior to surgical procedures in patients at a significant risk

for medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw.

Special Circumstances

The 2007 AHA guidelines state that an antibiotic for

prophylaxis should be administered in a single dose before

the procedure (3,4). However, in the event that the dosage

of antibiotic is inadvertently not administered before the

procedure, it may be administered up to two hours after the

procedure. For patients already receiving an antibiotic that

is also recommended for IE prophylaxis, then a drug should

be selected from a different class; for example, a patient

already taking oral penicillin for other purposes may likely

have in their oral cavity viridans group streptococci that are

relatively resistant to beta-lactams.

16

AAE Quick Reference Guide on Antibiotic Prophylaxis 2017 Update | Page 3

In these situations, clindamycin, azithromycin or

clarithromycin would be recommended for AP. Alternatively

if possible, treatment should be delayed until at least 10 days

after completion of antibiotic to allow re-establishment of

usual oral flora. In situations where patients are receiving

long-term parenteral antibiotic for IE, the treatment should

be timed to occur 30 to 60 min after delivery of the parenteral

antibiotic; it is considered that parenteral antimicrobial

therapy is administered in such high doses that the high

concentration would overcome any possible low-level

resistance developed among oral flora (3,4).

APPENDIX C REFERENCES

1. Nishimura RA, Otto CM, Bonow RO, Carabello BA, Erwin

JP, 3rd, Fleisher LA, et al. 2017 AHA/ACC Focused Update

of the 2014 AHA/ACC Guideline for the Management

of Patients With Valvular Heart Disease: A Report of

the American College of Cardiology/American Heart

Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines.

Circulation 2017

2. ADA. Antibiotic prophylaxis prior to dental procedures.

Oral Health Topics 2017 [cited 31st March 2017];

Available from: http://www.ada.org/en/member-center/

oral-health-topics/antibiotic-prophylaxis

3. Wilson W, Taubert KA, Gewitz M, Lockhart PB, Baddour

LM, Levison M, et al. Prevention of infective endocarditis:

guidelines from the American Heart Association: a

guideline from the American Heart Association Rheumatic

Fever, Endocarditis, and Kawasaki Disease Committee,

Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, and the

Council on Clinical Cardiology, Council on Cardiovascular

Surgery and Anesthesia, and the Quality of Care and

Outcomes Research Interdisciplinary Working Group.

Circulation 2007;116:1736-54.

4. Wilson W, Taubert KA, Gewitz M, Lockhart PB, Baddour

LM, Levison M, et al. Prevention of infective endocarditis:

guidelines from the American Heart Association: a

guideline from the American Heart Association Rheumatic

Fever, Endocarditis and Kawasaki Disease Committee,

Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, and the

Council on Clinical Cardiology, Council on Cardiovascular

Surgery and Anesthesia, and the Quality of Care and

Outcomes Research Interdisciplinary Working Group. J

Am Dent Assoc 2008;139 Suppl:3S-24S.

17

AMERICAN ACADEMY OF PEDIATRIC DENTISTRY

RECOMMENDATIONS: BEST PRACTICES 371

Purpose

e American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry (AAPD) recog-

nizes the increasing prevalence of antibiotic-resistant micro-

organisms. is guideline is intended to provide guidance in

the proper and judicious use of antibiotic therapy in the

treatment of oral conditions.

1

Methods

is guideline was originally developed by the Council on

Clinical Aairs and adopted in 2001. is document is a

revision of the previous version, last revised in 2009. e re-

vision was based upon a new systematic literature search of

the PubMed

®

/MEDLINE database using the terms: antibiotic

therapy, antibacterial agents, antimicrobial agents, dental trau-

ma, oral wound management, orofacial infections, periodontal

disease, viral disease, and oral contraception; elds: all; limits:

within the last 10 years, humans, English, clinical trials, birth

through age 18. One hundred sixty-ve articles matched these

criteria. Papers for review were chosen from this search and

from hand searching. When data did not appear sucient or

were inconclusive, recommendations were based upon expert

and/or consensus opinion by experienced researchers and

clinicians.

Background

Antibiotics are benecial in patient care when prescribed and

administered correctly for bacterial infections. However, the

widespread use of antibiotics has permitted common bacteria

to develop resistance to drugs that once controlled them.

1-3

Drug resistance is prevalent throughout the world.

3

Some

microorganisms may develop resistance to a single anti-

microbial agent, while others develop multidrug-resistant

strains.

2,3

To diminish the rate at which resistance is increas-

ing, health care providers must be prudent in the use of

antibiotics.

1

Recommendations

Conservative use of antibiotics is indicated to minimize the

risk of developing resistance to current antibiotic regimens.

2,3

Practitioners should adhere to the following general princi-

ples when prescribing antibiotics for the pediatric population.

Oral wound management

Factors related to host risk (e.g., age, systemic illness, malnu-

trition) and type of wound (e.g., laceration, puncture) must

be evaluated when determining the risk for infection and

subsequent need for antibiotics. Wounds can be classied as

clean, potentially contaminated, or contaminated/dirty. Facial

lacerations may require topical antibiotic agents.

4

Intraoral

lacerations that appear to have been contaminated by extrinsic

bacteria, open fractures, and joint injury have an increased risk

of infection and should be covered with antibiotics.

4

If it is

determined that antibiotics would be benecial to the healing

process, the timing of the administration of antibiotics is

critical to supplement the natural host resistance in bacterial

killing. e drug should be administered as soon as possible for

the best result. e most eective route of drug administration

(intravenous vs. intramuscular vs. oral) must be considered.

e clinical eectiveness of the drug must be monitored. e

minimal duration of drug therapy should be ve days beyond

the point of substantial improvement or resolution of signs

and symptoms; this is usually a five- to seven-day course of

treatment dependent upon the specific drug selected.

5-7

In

light of the growing problem of drug resistance, the clinician

should consider altering or discontinuing antibiotics following

determination of either ineectiveness or cure prior to com-

pletion of a full course of therapy.

8

If the infection is not respon-

sive to the initial drug selection, a culture and susceptibility

testing of isolates from the infective site may be indicated.

Special conditions

Pulpitis/apical periodontitis/draining sinus tract/localized intra-

oral swelling

Bacteria can gain access to the pulpal tissue through caries,

exposed pulp or dentinal tubules, cracks into the dentin, and

defective restorations. If a child presents with acute symptoms

of pulpitis, treatment (i.e., pulpotomy, pulpectomy, or extrac-

tion) should be rendered. Antibiotic therapy usually is not

indicated if the dental infection is contained within the pulpal

tissue or the immediate surrounding tissue. In this case, the

Review Council

Council on Clinical Affairs

Latest Revision

2014

Use of Antibiotic Therapy for

Pediatric Dental

Patients

ABBREVIATION

AAPD: American Academy Pediatric Dentistry.

18

Copyright © 2017-18 by the American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry and reproduced with their permission.

372 RECOMMENDATIONS: BEST PRACTICES

REFERENCE MANUAL V 39

/

NO 6 17

/

18

child will have no systemic signs of an infection (i.e., no fever

and no facial swelling).

9,10

Consideration for use of antibiotics should be given in

cases of advanced non-odontogenic bacterial infections such

as staphylococcal mucositis, tuberculosis, gonococcal stoma-

titis, and oral syphilis. If suspected, it is best to refer patients

for culture, biopsy, or other laboratory tests for documentation

and denitive treatment.

Acute facial swelling of dental origin

A child presenting with a facial swelling or facial cellulitis sec-

ondary to an odontogenic infection should receive prompt

dental attention. In most situations, immediate surgical inter-

vention is appropriate and contributes to a more rapid cure.

12

e clinician should consider age, the ability to obtain adequate

anesthesia (local vs. general), the severity of the infection, the

medical status, and any social issues of the child.

11,12

Signs

of systemic involvement (i.e., fever, asymmetry, facial swelling)

warrant emergency treatment. Intravenous antibiotic therapy

and/or referral for medical management may be indicated.

9-11

Penicillin remains the empirical choice for odontogenic

infections; however, consideration of additional adjunctive

antimicrobial therapy (i.e., metronidazole) can be given where

there is anaerobic bacterial involvement.

8

Dental trauma

Systemic antibiotics have been recommended as adjunc-

tive therapy for avulsed permanent incisors with an open or

closed apex.

14-17

Tetracycline (doxycycline twice daily for seven

days) is the drug of choice, but consideration of the child’s

age must be exercised in the systemic use of tetracycline due

to the risk of discoloration in the developing permanent

dentition.

13,14

Penicillin V or amoxicillin can be given as an

alternative.

14,15,17

e use of topical antibiotics to induce pulpal

revascularization in immature non-vital traumatized teeth

has shown some potential.

14,15,17,18

However, further random-

ized clinical trials are needed.

19-21

For luxation injuries in the

primary dentition, antibiotics generally are not indicated.

22,23

Antibiotics can be warranted in cases of concomitant soft

tissue injuries (see Oral wound management) and when

dictated by the patient’s medical status.

Pediatric periodontal diseases

Dental plaque-induced gingivitis does not require antibiotic

therapy. Pediatric patients with aggressive periodontal diseases

may require adjunctive antimicrobial therapy in conjunction

with localized treatment.

24

In pediatric periodontal diseases

associated with systemic disease (e.g., severe congenital neutro-

penia, Papillon-Lefèvre syndrome, leukocyte adhesion de-

ciency), the immune system is unable to control the growth

of periodontal pathogens and, in some cases, treatment may

involve antibiotic therapy.

24,25

e use of systemic antibiotics

has been recommended as adjunctive treatment to mechanical

debridement in patients with aggressive periodontal disease.

24,25

In severe and refractory cases, extraction is indicated.

24,25

Cul-

ture and susceptibility testing of isolates from the involved

sites are helpful in guiding the drug selection.

24,25

Viral diseases

Conditions of viral origin such as acute primary herpetic gin-

givostomatitis should not be treated with antibiotic therapy

unless there is strong evidence to indicate that a secondary

bacterial infection exists.

26

Salivary gland infections

Many salivary gland infections, following conrmation of

bacterial etiology, will respond favorable to antibiotic therapy.

Acute bacterial parotitis has two forms: hospital acquired and

community acquired.

27

Both can be treated with antibiotics.

Hospital acquired usually requires intravenous antibiotics; oral

antibiotics are appropriate for community acquired. Chronic

recurrent juvenile parotitis generally occurs prior to puberty.

Antibiotic therapy is recommended and has been successful.

27

For both acute bacterial submandibular sialadenitis and chro-

nic recurrent submandibular sialadenitis, antibiotic therapy is

included as part of the treatment.

27

Oral contraceptive use

Whenever an antibiotic is prescribed to a female patient

taking oral contraceptives to prevent pregnancy, the patient

must be advised to use additional techniques of birth control

during antibiotic therapy and for at least one week beyond the

last dose, as the antibiotic may render the oral contraceptive

ineective.

28,29

Rifampicin has been documented to decrease

the eectiveness of oral contraceptives.

28,29

Other antibiotics,

particularly tetracycline and penicillin derivatives, have been

shown to cause signicant decrease in the plasma concentra-

tions of ethinyl estradiol, causing ovulation in some individuals

taking oral contraceptives.

28,29

Caution is advised with the

concomitant use of antibiotics and oral contraceptives.

28,29

References

1. Wilson W, Taubert KA, Gevitz M, et al. Prevention of in-

fective endocarditis: Guidelines from the American Heart

Association—A Guideline From the American Heart As-

sociation Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis and Kawasaki

Disease Committee, Council on Cardiovascular Disease

in the Young, and the Council on Clinical Cardiology,

Council on Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia Anes-

thesia, and the Quality of Care and Outcomes Research

Interdisciplinary Working Group. Circulation 2007;

116(15):1736-54. E-published April 19, 2007. Erratum

in: Circulation 2007;116(15):e376-e7.

2. Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Antibiotic/

Antimicrobial Resistance. Available at: “http://www.

cdc.gov/drugresistance/”. Accessed August 5, 2014.

3. Costelloe C, Metcalfe C, Lovering A, et al. Effect of

antibiotic prescribing in primary care on antimicrobial

resistance in individual patients: Systematic review and

meta-analysis. BMJ 2010;340:c2096.

19

AMERICAN ACADEMY OF PEDIATRIC DENTISTRY

RECOMMENDATIONS: BEST PRACTICES 373

4. Nakamura Y, Daya M. Use of appropriate antimicro-

bials in wound management. Emerg Med Clin North

Am 2007;25(1):159-76.

5. Wickersham RM, Novak KK, Schweain SL, et al. Sys-

temic anti-infectives. In: Drug Facts and Comparisons.

St. Louis, Mo.: 2004:1217-336.

6. Kuriyama T, Karasawa T, Nakagawa K, Saiki Y, Yamamoto

E, Nakamura S. Bacteriological features and antimicro-

bial susceptibility in isolates from orofacial odontogenic

infections. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol

Endod 2000;90(5):600-8.

7. Prieto-Prieto J, Calvo A. Microbiological basis of oral

infections and sensitivity to antibiotics. Med Oral Patol

Oral Cir Bucal 2004;9(suppl S):11-8.

8. Flynn T. What are the antibiotics of choice for odonto-

genic infections, and how long should the treatment

course last? Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin N Am 2011;23

(4):519-36.

9. Maestre Vera Jr. Treatment options in odontogenic infec-

tion. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal 2004;9(suppl S):

19-31.

10. Keenan JV, Farman AG, Fedorowicz Z, Newton JT. A

Cochrane system review nds no evidence to support the

use of antibiotics for pain relief in irreversible pulpitis.

J Endod 2006;32(2):87-92.

11. ikkurissy S, Rawlins JT, Kumar A, Evans E, Casamas-

simo PS. Rapid treatment reduces hospitalization for

pediatric patients with odontogenic-based cellulitis. Am J

Emerg Med 2010;28(6):668-672.

12. Johri A, Piecuch JF. Should teeth be extracted immedia-

tely in the presence of acute infection? Oral Maxillofac

Surg Clin North Am 2011;23(4):507-11.

13. Rega AJ, Aziz SR, Ziccardi VB. Microbiology and Anti-

biotic Sensitivities of Head and Neck Space Infections of

Odontogentic Origin. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2006;64

(9):1377-1380.

14. Andreasen JO, Andreasen FM. Avulsions. In: Textbook

and Color Atlas of Traumatic Injuries to the Teeth, 4th

ed. Copenhagen, Denmark: Blackwell Munksgaard;

2007:461, 478-88.

15. Dentaltraumaguide.org. e Dental Trauma Guide 2010.

Permanent Avulsion Treatment. Available at “http://

www.dentaltraumaguide.org/Permanent_Avulsion_

Treatment.aspx”. Accessed October 1, 2013.

16. DiAngelis AJ, Andreasen JO, Ebelseder KA, et al. In-

ternational Association of Dental Traumatology Guide-

lines for the management of traumatic dental injuries:

1 – Fractures and luxations of permanent teeth. Dent

Traumatol 2012;28:2-12.

17. Andersson L, Andreasen JO, Day P, et al. International

Association of Dental Traumatology Guidelines for the

management of traumatic dental injuries: 2 – Avulsion

of permanent teeth. Dent Traumatol 2012;28:88-96.

18. McIntyre JD, Lee JY, Tropte M, Vann WF Jr. Manage-

ment of avulsed permanent incisors: A comprehensive

update. Pediatr Dent 2007;29(1):56-63.

19. Hargreaves KM, Diogenes A, Teixeira FB. Treatment

options: Biological basis of regenerative endodontic pro-

cedures. Pediatr Dent 2013;35(2):129-40.

20. ibodeau B, Teixeira F, Yamauchi M, Caplan DJ, Trope

M. Pulp revascularization of immature dog teeth with

apcial periodontitis. J Endod 2007;36(6):680-9.

21. Shabahang S. Treatment options: Apexogenesis and

apexication. Pediatr Dent 2013;35(2):125-8.

22. Malmgren B, Andreasen JO, Flores MT, et al. Interna-

tional Association of Dental Traumatology Guidelines for

the management of traumatic dental injuries: III. Injuries

in the primary dentition. Dental Traumatology 2012;

28:174-82.

23. Dentaltraumaguide.org. e Dental Trauma Guide: Pri-

mary Teeth, 2010. Available at “http://www.dental

traumaguide.org/Primary_teeth.aspx.” Accessed October

1, 2013.

24. American Academy of Periodontology Research, Science

and erapy Committee. Periodontal diseases of children

and adolescents. J Periodontol 2003;74:1696-704.

25. Schmidt JC, Wlater C, Rischewski JR, Weiger R. Treat-

ment of periodontitis as a manifestation of neutropenia

with or without systemic antibiotics: A systematic review.

Pediatr Dent 2013;35(2):E54-E63.

26. American Academy of Pediatrics. Herpes simplex. In: Red

Book: 2003 Report of the Committee on Infectious Dis-

eases. 26th ed. Elk Grove Village, Ill: American Academy

of Pediatrics; 2003:344-53.

27. Carlson ER. Diagnosis and management of salivary gland

infections. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin N Am 2009;21

(3):293-312.

28. DeRossi SS, Hersh EV. Antibiotics and oral contracep-

tives. Pediatr Clin North Am 2002;46(4):653-64.

29. Becker DE. Adverse drug interactions. Anesth Prog 2011;

58(1):31-41.

20

Management of patients with prosthetic joints

undergoing dental procedures

Clinical Recommendation:

In general, for patients with prosthetic joint implants, prophylactic antibiotics are

not

recommended prior to dental procedures to prevent prosthetic joint infection.

For patients with a history of complications associated with their joint replacement surgery who are undergoing dental procedures

that include gingival manipulation or mucosal incision, prophylactic antibiotics should only be considered after consultation with

the patient and orthopedic surgeon.* To assess a patient’s medical status, a complete health history is always recommended when

making final decisions regarding the need for antibiotic prophylaxis.

Clinical Reasoning for the Recommendation:

• There is evidence that dental procedures are not associated with prosthetic joint implant infections.

• There is evidence that antibiotics provided before oral care do not prevent prosthetic joint implant infections.

• There are potential harms of antibiotics including risk for anaphylaxis, antibiotic resistance, and opportunistic infections

like Clostridium difficile.

• The benefits of antibiotic prophylaxis may not exceed the harms for most patients.

• The individual patient’s circumstances and preferences should be considered when deciding whether to prescribe prophylactic

antibiotics prior to dental procedures.

* In cases where antibiotics are deemed necessary, it is most appropriate that the orthopedic surgeon recommend the appropriate antibiotic regimen and when reasonable write the prescription.

Copyright © 2015 American Dental Association. All rights reserved. This page may be used, copied, and distributed

for non-commercial purposes without obtaining prior approval from the ADA. Any other use, copying, or distribution,

whether in printed or electronic format, is strictly prohibited without the prior written consent of the ADA.

Sollecito T, Abt E, Lockhart P, et al. The use of prophylactic antibiotics prior to dental procedures in patients with prosthetic joints: Evidence-based clinical practice guideline for dental practitioners — a report

of the American Dental Association Council on Scientific Affairs. JADA. 2015;146(1):11-16.

21

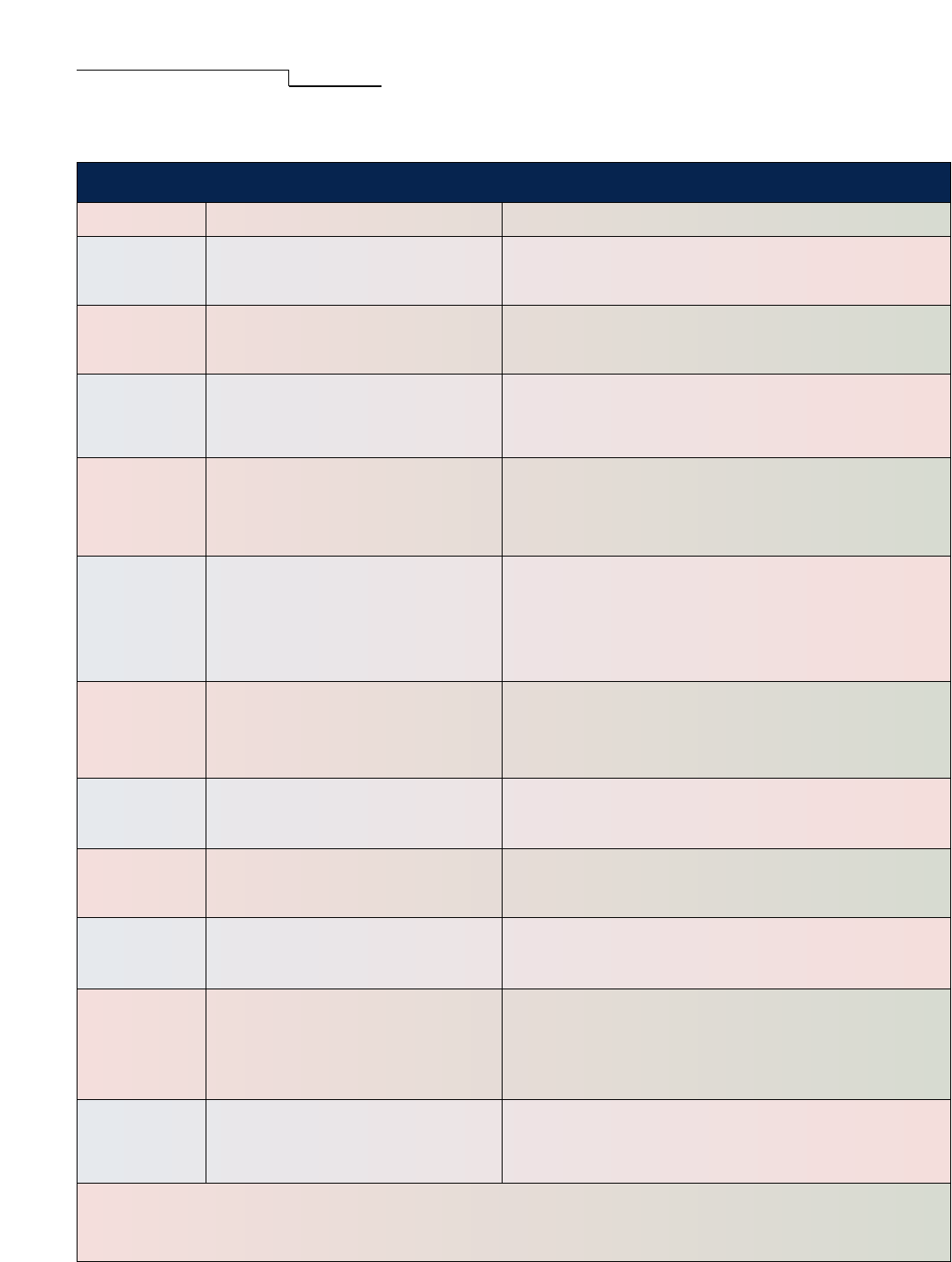

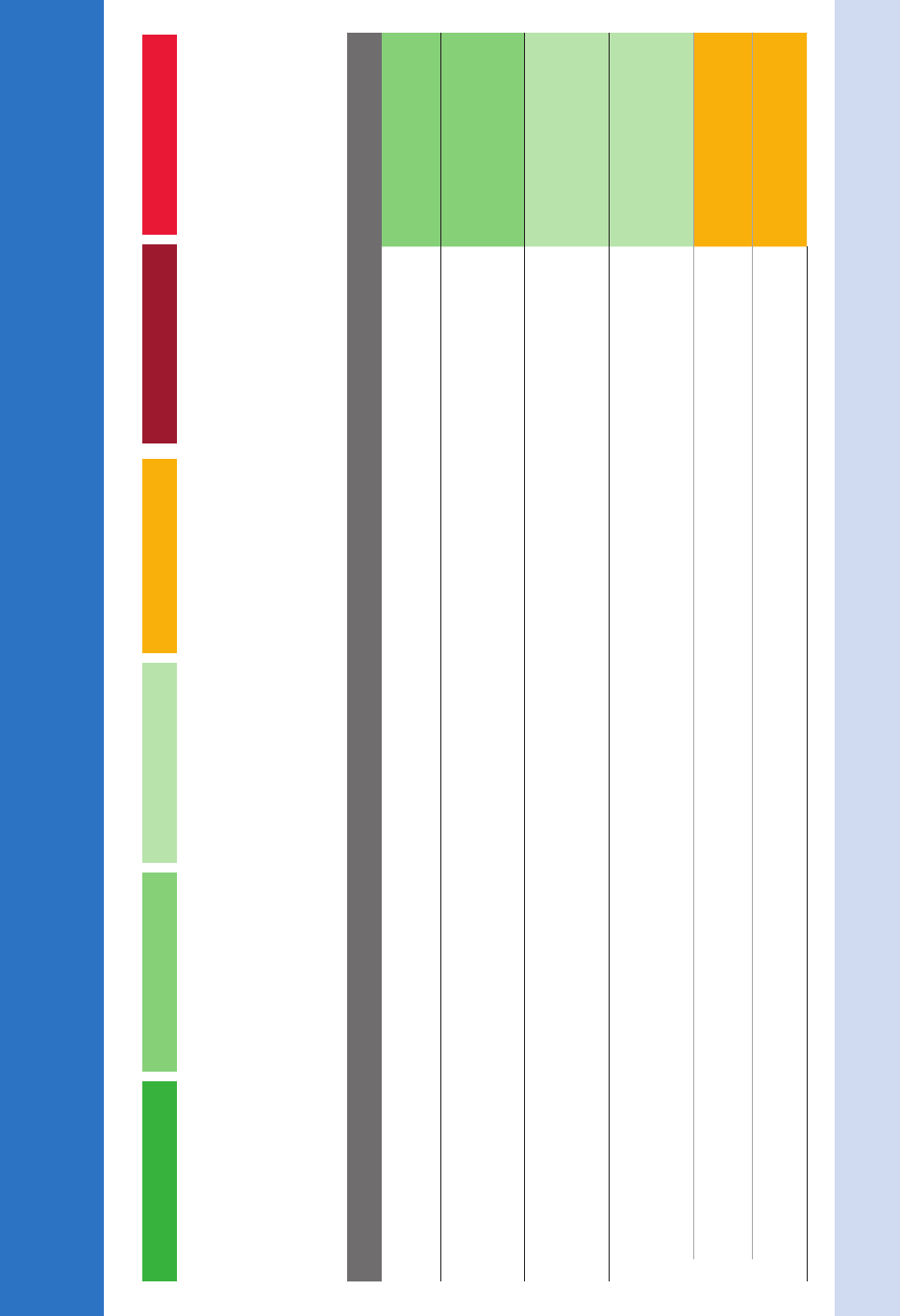

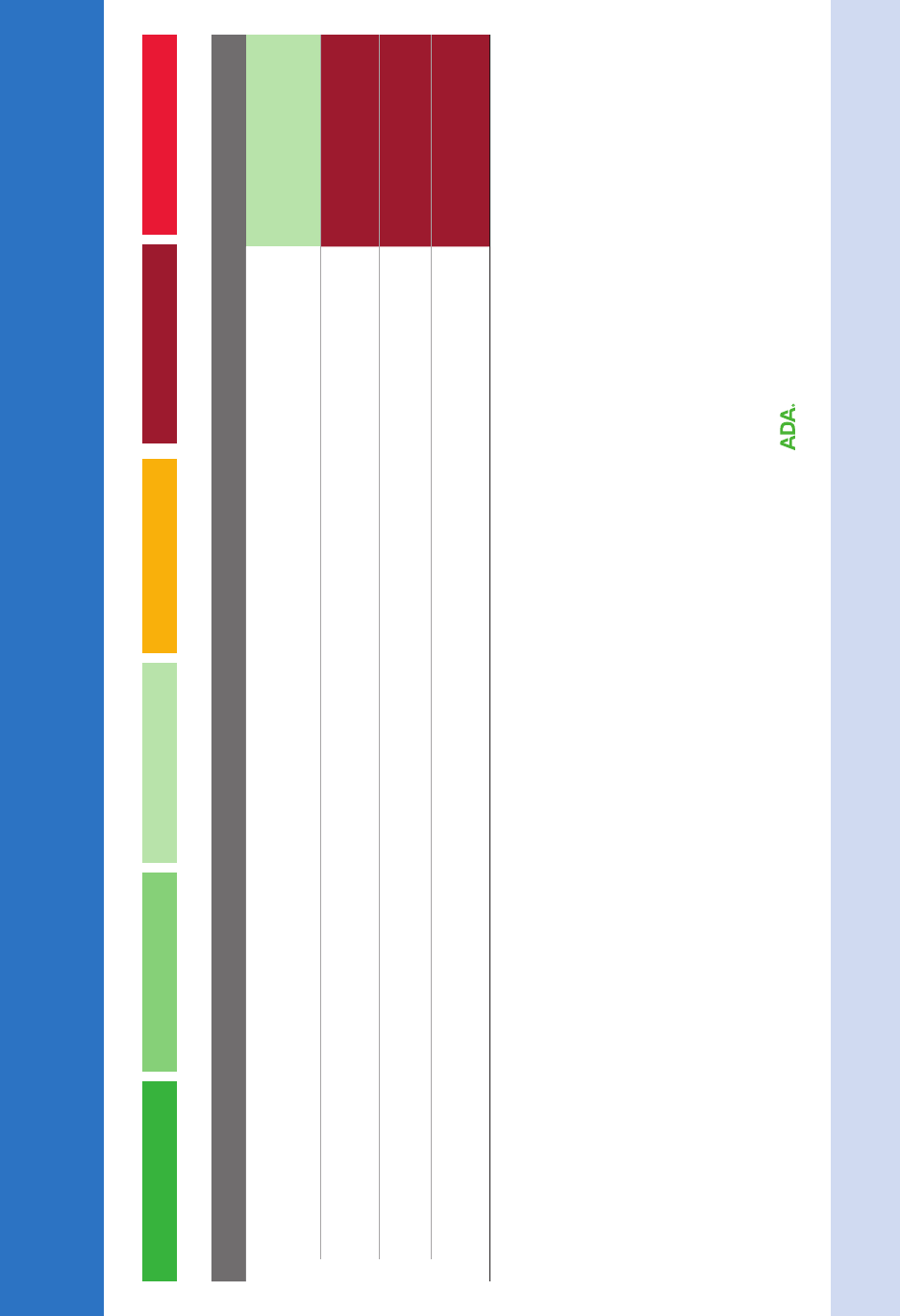

Nonsurgical Treatment of Chronic Periodontitis by Scaling and Root

Planing with or without Adjuncts: Clinical Practice Guideline

1,2

Strength of recommendations: Each recommendation is based on the best available evidence. The level of evidence available to support each recommendation may differ.

Evidence strongly supports

providing this intervention. There

is a high level of certainty of

benefits, and the benefits

outweigh the potential harms.

Strong

Expert Opinion suggests this

intervention can be implemented,

but there is a low level of certainty

of benefits and there is uncertainty

in the benefit to harm balance.

Expert Opinion For

Evidence favors providing this

intervention. Either there is a high

level of certainty of benefits, but

the benefits are balanced with

the potential harms OR there

is a moderate level of certainty

of benefits, and the benefits

outweigh the potential for harms.

In Favor

Expert Opinion suggests this

intervention NOT be implemented

because there is a low level of

certainty that there is no benefit

or the potential harms outweigh

benefits.

Expert Opinion Against

Evidence suggests implementing

this intervention only after alterna-

tives have been considered. There

is a moderate level of certainty of

benefits, and either the benefits

are balanced with potential harms

or there is uncertainty in the

magnitude of the benefit.

Weak

Evidence suggests not

implementing this intervention

or discontinuing ineffective

procedures. There is moderate

or high certainty that there are

no benefits and/or the potential

harms outweigh the benefits.

Against

Clinical Recommendation Strength

Scaling and root planing (no adjuncts)

For patients with chronic periodontitis, clinicians should consider scaling and root planing (SRP) as the initial treatment.

In Favor

SRP with systemic sub-antimicrobial dose doxycycline

For patients with moderate to severe chronic periodontitis, clinicians may consider systemic sub-antimicrobial dose doxycycline (20 mg twice a day) for

3 to 9 months as an adjunct to SRP with a small net benefit expected.

In Favor

SRP with systemic antimicrobials

For patients with moderate to severe chronic periodontitis, clinicians may consider systemic antimicrobials as an adjunct to SRP with a small net benefit

expected.

Weak

SRP with locally-delivered antimicrobials

For patients with moderate to severe chronic periodontitis, clinicians may consider locally delivered chlorhexidine chips as an adjunct to SRP with a

moderate net benefit expected.

Weak

For patients with moderate to severe chronic periodontitis, clinicians may consider locally delivered doxycycline hyclate gel as an adjunct to SRP, but

the net benefit is uncertain.

Expert Opinion For

For patients with moderate to severe chronic periodontitis, clinicians may consider locally delivered minocycline microspheres as an adjunct to SRP,

but the net benefit is uncertain.

Expert Opinion For

1 Smiley CJ, Tracy SL, Abt E, Michalowicz B, et al. Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guideline on the Nonsurgical Treatment of Chronic Periodontitis by Scaling and Root Planing with or without Adjuncts. JADA 2015; 146 (7):525-535.

2 Smiley CJ, Tracy SL, Abt E, Michalowicz B, et al. Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis on the Nonsurgical Treatment of Chronic Periodontitis by Scaling and Root Planing with or without Adjuncts. JADA 2015; 146 (7):508-524.

©2015 American Dental Association. All rights reserved.

22

Copyright © 2015 American Dental Association. All rights reserved. Adapted with permission. To see full text of this article, please go to JADA/ADA.org/cgi/content/ This page may be used, copied, and distributed for

non-commercial purposes without obtaining prior approval from the ADA. Any other use, copying, or distribution, whether in printed or electronic format, is strictly prohibited without the prior written consent of the ADA.

Center for Evidence-Based Dentistry

™

Nonsurgical Treatment of Chronic Periodontitis by Scaling and Root

Planing with or without Adjuncts: Clinical Practice Guideline

1,2

Clinical Recommendation Strength

SRP with nonsurgical use of lasers

For patients with moderate to severe chronic periodontitis, clinicians may consider photodynamic therapy (PDT) using diode lasers as an adjunct

to SRP with a moderate net benefit expected.

Weak

For patients with moderate to severe chronic periodontitis, clinicians should be aware that the current evidence shows no net benefit from diode

(non-PDT) lasers when used as an adjunct to SRP.

Expert Opinion Against

For patients with moderate to severe chronic periodontitis, clinicians should be aware that the current evidence shows no net benefit from Nd:YAG

lasers when used as an adjunct to SRP.

Expert Opinion Against

For patients with moderate to severe chronic periodontitis, clinicians should be aware that the current evidence shows no net benefit from erbium

lasers when used as an adjunct to SRP.

Expert Opinion Against

Strength of recommendations: Each recommendation is based on the best available evidence. The level of evidence available to support each recommendation may differ.

Strong Expert Opinion For In Favor Expert Opinion Against Weak Against

23

24

3. Track and Report

Tracking and reporting antibiotic prescribing can guide changes in practice and be

used to assess progress in improving antibiotic prescribing. Dentists can track and

report antibiotic prescribing practices by doing the following:

Complete the enclosed survey

This tool is intended to help you assess your facility’s current antibiotic prescribing

practices and identify areas for improvement. It will also help IDPH learn how to

support dentists’ antibiotic stewardship efforts. Please complete this brief survey

online at http://tinyurl.com/survey4dentists by December 22, 2017.

Rather complete the survey by mail? A postage-paid envelope has been included for

your convenience. You may also fax the completed survey to: 312-814-1953.

Participate in continuing medical education and quality improvement activities to track

and improve antibiotic prescribing

Attend the Annual Illinois Summit on Antimicrobial Stewardship next summer. This

annual event convenes clinicians across health care settings to discuss antibiotic

stewardship best practices. More information on the summit will be shared in spring

2018. To be added to the e-mail list, contact: [email protected]v.

Implement a tracking and reporting system in your facility to monitor antibiotic

prescribing

Refer to CDC’s resources on tracking at: https://tinyurl.com/CDCtrack.

25

4. Educate

Dentists can educate patients about the potential harms of antibiotic treatment with

the following tools:

Antibiotic Safety: Do’s & Don’ts at the Dentist (page 26)

Download here: http://tinyurl.com/patiented1.

What is antibiotic prophylaxis? (page 27)

Download here: http://tinyurl.com/patiented2.

What is Infective endocarditis? (page 28)

Download here: http://tinyurl.com/patiented3.

Improving Antibiotic Use (page 30)

Download here: http://tinyurl.com/patiented4.

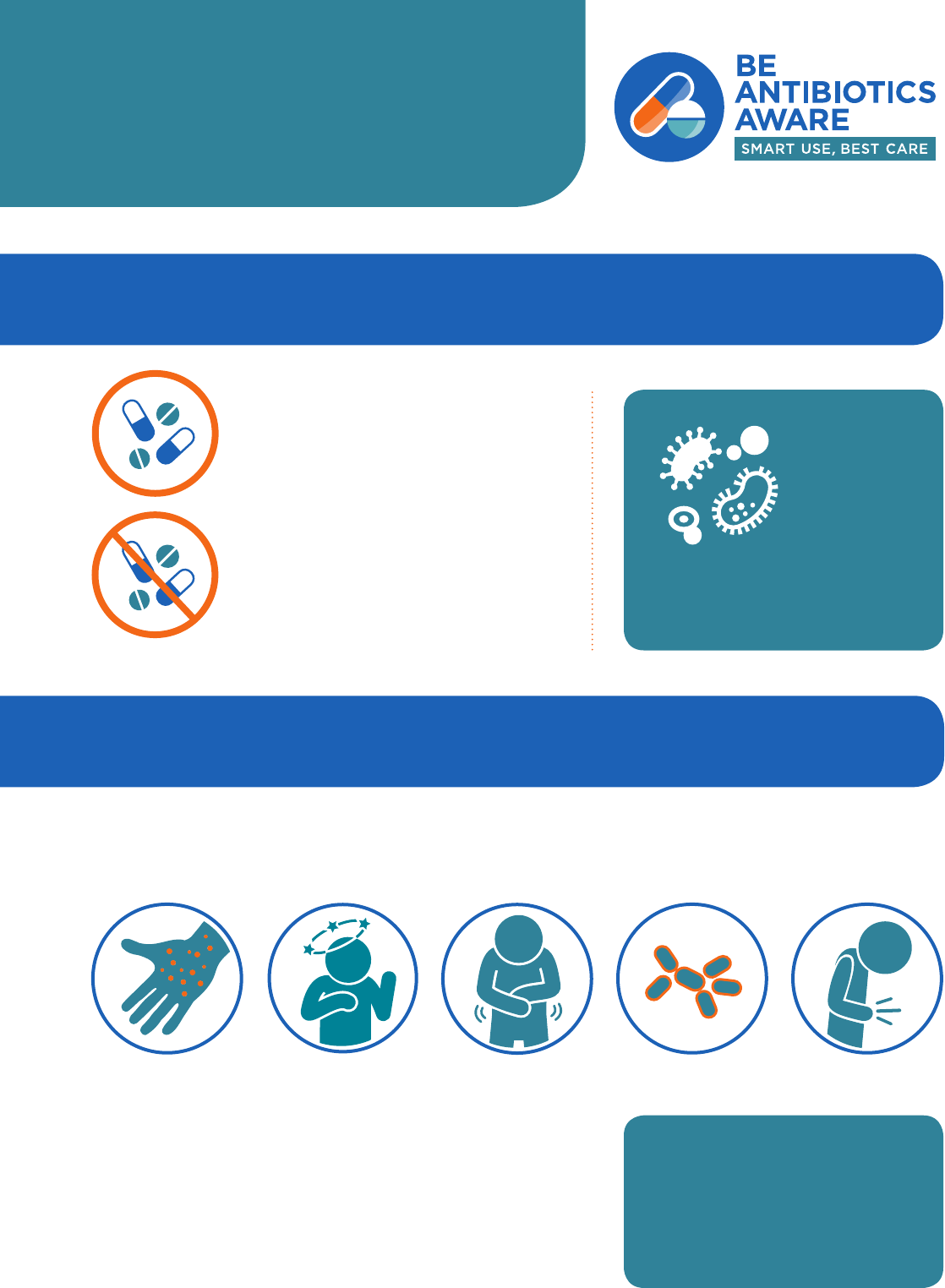

Antibiotic Safety: Do’s and Don’ts at the Dentist

DO

9 DO tell your dentist if you

have any drug allergies or

medical conditions.

9 DO tell your dentist about

any medications, vitamins, or

herbal supplements you are

taking.

9 DO ask how some mouth

infection can be treated

without antibiotics.

9 DO take your antibiotics

exactly as prescribed.

9 DO tell your dentist if you

have side effects, such as

frequent diarrhea, while

taking, or shortly after

stopping antibiotics.

DO NOT

X DO NOT skip doses or stop

taking your antibiotics

without consulting your

dentist.

X DO NOT save unused

antibiotics for future use or

give antibiotics to others.

X DO NOT take antibiotics

prescribed for others.

X DO NOT pressure your

dentist to prescribe an

antibiotic. Instead, ask your

dentist how you can feel

better even if antibiotics are

not prescribed.

CS267104

https://www.cdc.gov/getsmart/community/downloads/dos-and-donts---final.pdf

26

What is antibiotic

prophylaxis?

A

ntibiotics usually are used to treat bacterial

infections. Sometimes, though, dentists or

physicians suggest taking antibiotics before

treatment to decrease the chance of infection.

This is called antibiotic prophylaxis.

During some dental treatments, bacteria from the

mouth enter the bloodstream. In most people, the im-

mune system kills these bacteria. There is concern,

though, that in some patients, bacteria from the mouth

can travel through the bloodstre am and cause an infec-

tion somewhere else in the body. Antibiotic prophylaxis

may offer these people extra protection.

1

WHO MIGHT BENEFIT FROM ANTIBIOTIC

PROPHYLAXIS?

People with certain heart conditions may be at increased

risk of developing infective endocarditis (IE)—an infec-

tion of the lining of the heart or heart valves. To protect

against IE, or limit its effects should the infection

develop, the American Heart Association suggests that

antibiotic prophylaxis be considered for people who

have

1

-

an artificial heart valve or who have had a heart valve

repaired with a prosthetic material;

-

a history of IE;

-

a heart transplant that develops a valve problem;

-

certain heart conditions that are congenital (present

from birth), including

n unrepaired or incompletely repaired cyanotic

congenital heart disease, including those with palliative

shunts and conduits;

n a completely repaired congenital heart defect with

prosthetic material or device, whether placed by surgery

or by catheter intervention, during the first 6 months

after the procedure;

n any repaired congenital heart disease with residual

defect at the site or adjacent to the site of a prosthetic

patch or prosthetic device.

WHAT ABOUT PEOPLE WHO HAVE HAD HIP OR KNEE

REPLACEMENT SURGERY?

The American Dental Association does not routinely

recommend antibiotic prophylaxis for people who have

had a hip, knee, or other joint replaced.

2

People who

have had joint replacement surgery and have a weakened

immune system—meaning that they are less able to fight

infections—should talk to their dentist and their ortho-

pedic surgeon to see if antibiotic prophylaxis is recom-

mended. Conditions such as diabetes, rheumatoid

arthritis, or cancer and medications such as steroid s

and those used in chemotherapy can affect your ability to

fight infections.

WHY IS ANTIBIOTIC PROPHYLAXIS NOT USED FOR

EVERY PATIENT?

Antibiotic prophylaxis is not right for everyone and—

like any medicine—antibiotics should only be used when

the potential benefits outweigh the risks of taking them.

For example, consider that infections after dental treat-

ment are not common and that, in some people, anti-

biotics can have side effects. Side effects associated with

taking antibiotics include stomach upset, diarrhea, and

allergic reactions, some of which can be life threatening.

In addition, using antibiotics too often or incorrectly can

allow bacteria to become resistant to those medications.

Therefore, it is important to use antibiotic prophylaxis in

only those people at greatest risk of developing an

infection after dental treatment.

WHAT CAN YOU DO?

Tell your dentist about any changes in your health since

your last visit and make sure he or she knows about all

medications you are taking. With this information in

hand, your dentist can talk to you and your physician

about whether you could benefit from antibiotic

prophylaxis.

Good home care is key to good dental health. Be

sure to brush you r teeth twice a day with a fluoride

toothpaste, clean between your teeth once a day, eat

a balanced diet, and visit your dentist regularly.

n

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.adaj.2016.03.016

Prepared by Anita M. Mark, manager, Scientific Information Develop-

ment, ADA Science Institute, American Dental Association, Chicago, IL.

Disclosure. Ms. Mark did not report any disclosures.

Copyright Ó 2016 American Dental Association. Unlike other portions of

JADA, the print and online versions of this page may be reproduced as a

handout for patients without reprint permission from the ADA Publishing

Division. Any other use, copying, or distribution of this material, whether in

printed or electronic form, including the copying and posting of this ma-

terial on a website is prohibited without prior written consent of the ADA

Publishing Division.

“For the Patient” provides general information on dental treatments. It is

designed to prompt discussion between dentist and patient about treatment

options and does not substitute for the dentist’s professional assessment

based on the individual patient’s needs and desires.

1. Wilson W, Taubert KA, Gewitz M, et al. Prevention of infective

endocarditis: guidelines from the American Heart Association: a guideline

from the American Heart Association Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis and

Kawasaki Disease Committee, Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the

Young, and the Council on Clinical Cardiology, Council on Cardiovascular

Surgery and Anesthesia, and the Quality of Care and Outcomes Research

Interdisciplinary Working Group. JADA. 2008;139(suppl):3S-24S.

2. Sollecito TP, Abt E, Lockhart PB, et al. The use of prophylactic anti-

biotics prior to dental procedures in patients with prosthetic joints:

evidence-based clinical practice guideline for dental practitioners—a report

of the American Dental Association Council on Scientific Affairs. JADA.

2015;146(1):11-16.e8.

FOR THE PATIENT

526 JADA 147(6) http://jada.ada.org June 2016

27

(continued)

ANSWERS

by

heart

What’s the role of bacteria?

Certain bacteria normally live on parts of your body.

They live in or on the:

• mouth and upper respiratory system.

• intestinal and urinary tracts.

• skin.

Bacteria can get in the bloodstream. This is called

bacteremia. These bacteria can settle on abnormal,

damaged, or prosthetic heart valves or other damaged

heart tissue. If this happens, they can damage or even

destroy the heart valves.

The heart valves are important in guiding blood ow

through the heart. They work like doors to keep the

blood owing in one direction. If they become damaged,

the results can be very serious.

A brief bacteremia can occur after many routine daily

activities such as:

• tooth brushing and ossing.

• use of wooden toothpicks.

• use of water picks.

• chewing food.

It can also result after certain surgical and dental

procedures. Not all bacteria cause endocarditis, though.

What’s the heart’s role?

People who have certain heart conditions are at

increased risk of developing infective endocarditis.

People with the highest risk for poor outcomes from

IE may be prescribed antiobiotics prior to dental

procedures to reduce their risk of developing IE.

Heart conditions that put people at the highest risk for

poor outcomes from IE include:

• articial (prosthetic) heart valves or heart valves

repaired with articial material

• a history of infective endocarditis

• some kinds of congenital heart defects

• abnormality of the heart valves after a heart transplant

People who’ve had IE before are at higher risk of getting

Infective (bacterial) endocarditis (IE) is an

infection of either the heart’s inner lining

(endocardium) or the heart valves. Infective

endocarditis is a serious — and sometimes

fatal — illness. Two things increase risk for

it to occur: pathogens such as bacteria

or fungi in the blood and certain high-risk

heart conditions.

Men, women and children of all racial

and ethnic groups can get it. In the

United States, there are up to 34,000

hospital discharges r

elated to IE each year.

What Is Infective

Endocarditis?

Cardiovascular Conditions

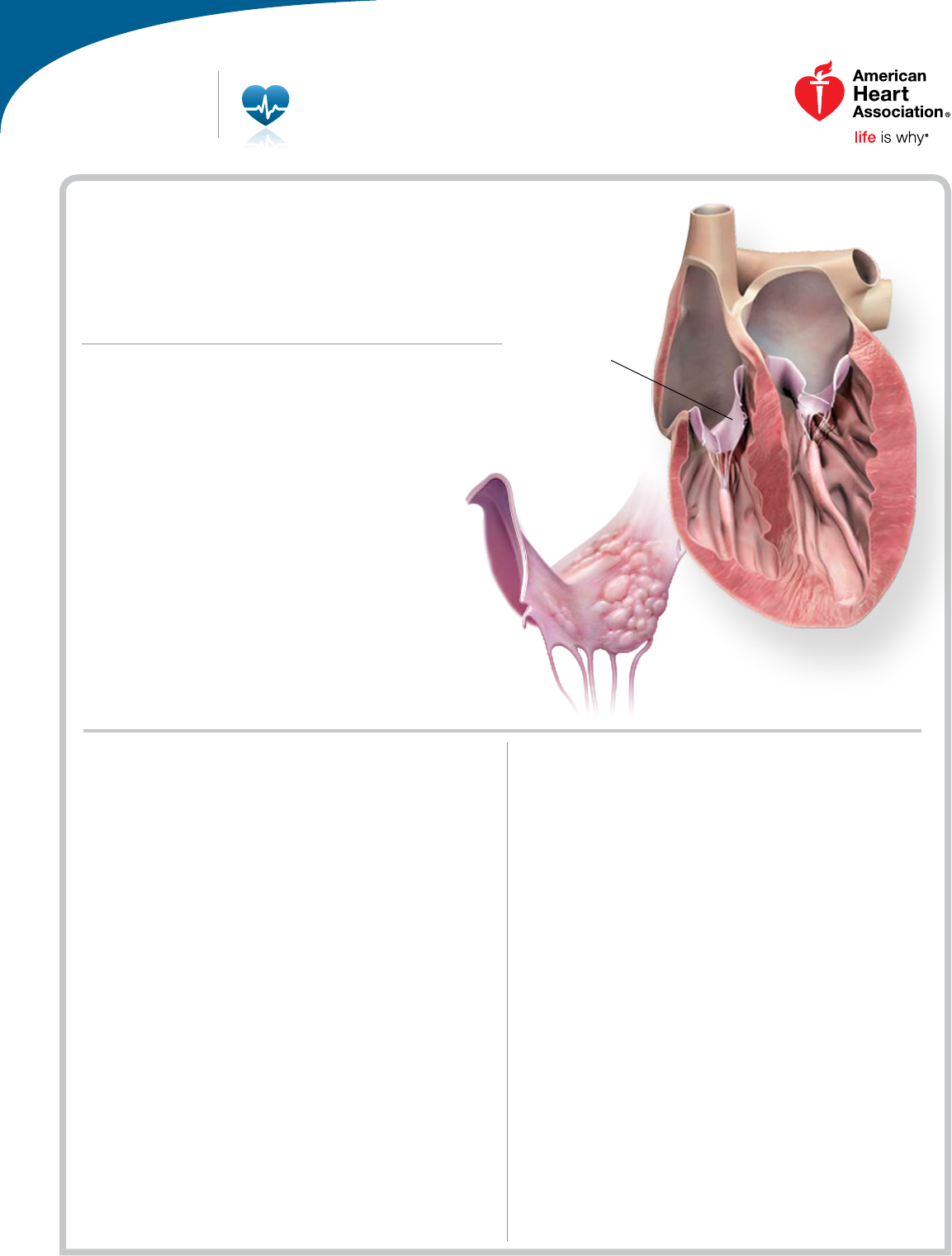

Below: closeup

of a tricuspid

valve damaged

by infective

endocarditis

Healthy

tricuspid

valve

28

Cardiovascular Conditions

ANSWERS

by

heart

What Is Infective Endocarditis?

ANSWERS

by

heart

it again. This is true even when they don’t have heart

disease.

How can infective endocarditis be

prevented?

Not all cases can be prevented. That’s because we don’t

always know when an infection will occur.

For patients whose heart conditions put them at the

highest risk for adverse events from IE, the American

Heart Association (AHA) recommends antibiotics before

certain dental procedures. These include procedures that

involve manipulation of gingival tissue or the periapical

region of teeth, or perforation of the oral mucosa.

However, for most patients, antibiotics are not needed.

The AHA has an endocarditis wallet card in English

and Spanish. People who have been told that they need

to take antibiotics should carry it. You can get it from

your doctor or on our Web site,

heart.org. Show the card

to your dentist or physician. It will help them take the

precautions needed to protect your health.

Keeping your mouth clean and healthy and maintaining

regular dental care may reduce the chance of bacteremia

from routine daily activities.

Take a few minutes to